第17回IIBC高校生英語エッセイコンテストの表彰式を、

2025年11月23日にホテルニューオータニで開催しました。

今年度も個人部門および団体部門において、

過去最多となる応募をいただきました(個人部門:

224校・433作品、団体部門:68校・3,936作品)。

ありがとうございました。

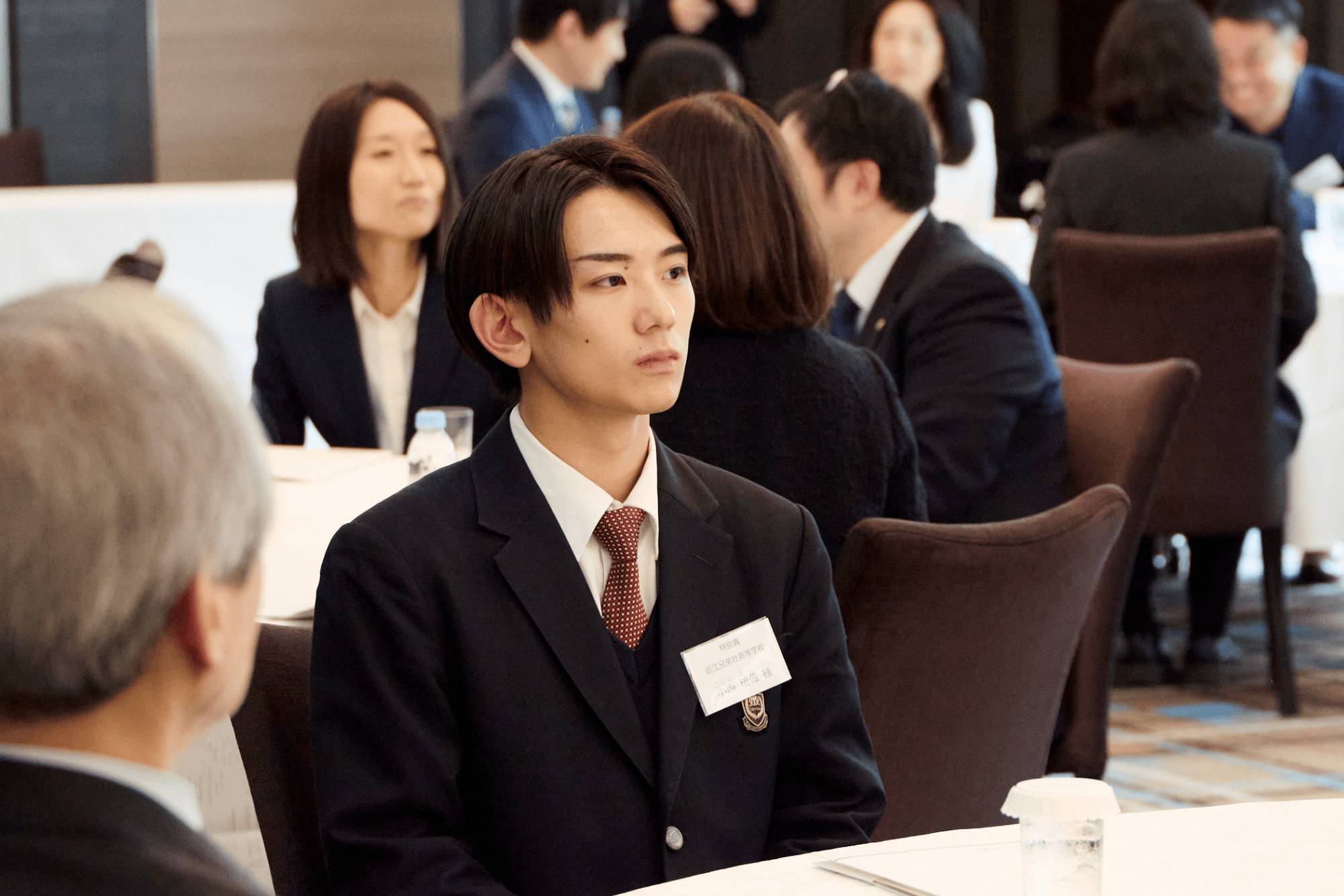

第17回(2025年度)

Thank you without saying

仙台育英学園高等学校 1年

圡屋 遼人

仙台育英学園高等学校 1年

圡屋 遼人

この度は、最優秀賞を頂き大変光栄です。小学生の時、障がいのある同級生が言葉ではなく静かな行動で感謝を伝えてくれた経験から、「コミュニケーションの本質とは思いであること」「沈黙の大切さ」を書きました。

英語が身近でなかった私にとって執筆は苦労しましたが、私の思いが伝わり、大変嬉しく存じます。沈黙は言葉があるからこそ力を持ちます。英語においてもまず言葉を学び、沈黙にも耳を傾けていきたいと思います。

今まで私の英語学習に協力してくださった全ての方々に心から御礼を申し上げます。

※日米協会会長賞を同時受賞

Flight

洗足学園高等学校 5年

菅原 俐亜

洗足学園高等学校 5年

菅原 俐亜

この度は優秀賞をいただき、大変光栄です。今回のエッセイでは、聴覚に障がいのあるダンサーとの出会いを通して、言葉を超えた心のつながりについて綴りました。名前さえ聞くことができなかった彼が、これほどまでに私の考え方を変えてくれたことへの感謝が、エッセイを通して少しでも伝われば嬉しく思います。また、読んでくださる皆さまにも、私がその瞬間に抱いた好奇心や、込めた謎めいた要素を感じ取っていただければ幸いです。このような貴重な機会を頂き、心より感謝申し上げます。

HUG - Healing, Understanding, Giving

松山東雲中学・高等学校 3年

西宮 莉杏

松山東雲中学・高等学校 3年

西宮 莉杏

この度はこのような素晴らしい賞をいただくことができ、とても光栄に思います。自分の思いをエッセイに綴っていく過程で、「ハグ」について調べる機会が多くあり、たくさんの学びを得ることができました。ハグと平和。無縁のものだと思っていたものがつながっているという、エッセイを通して見つけた私なりの答えですが、多くの人と共有できれば嬉しく思います。最後に、ご指導してくださった先生、そして応援してくれた家族に深く感謝します。

※日米協会会長賞を同時受賞

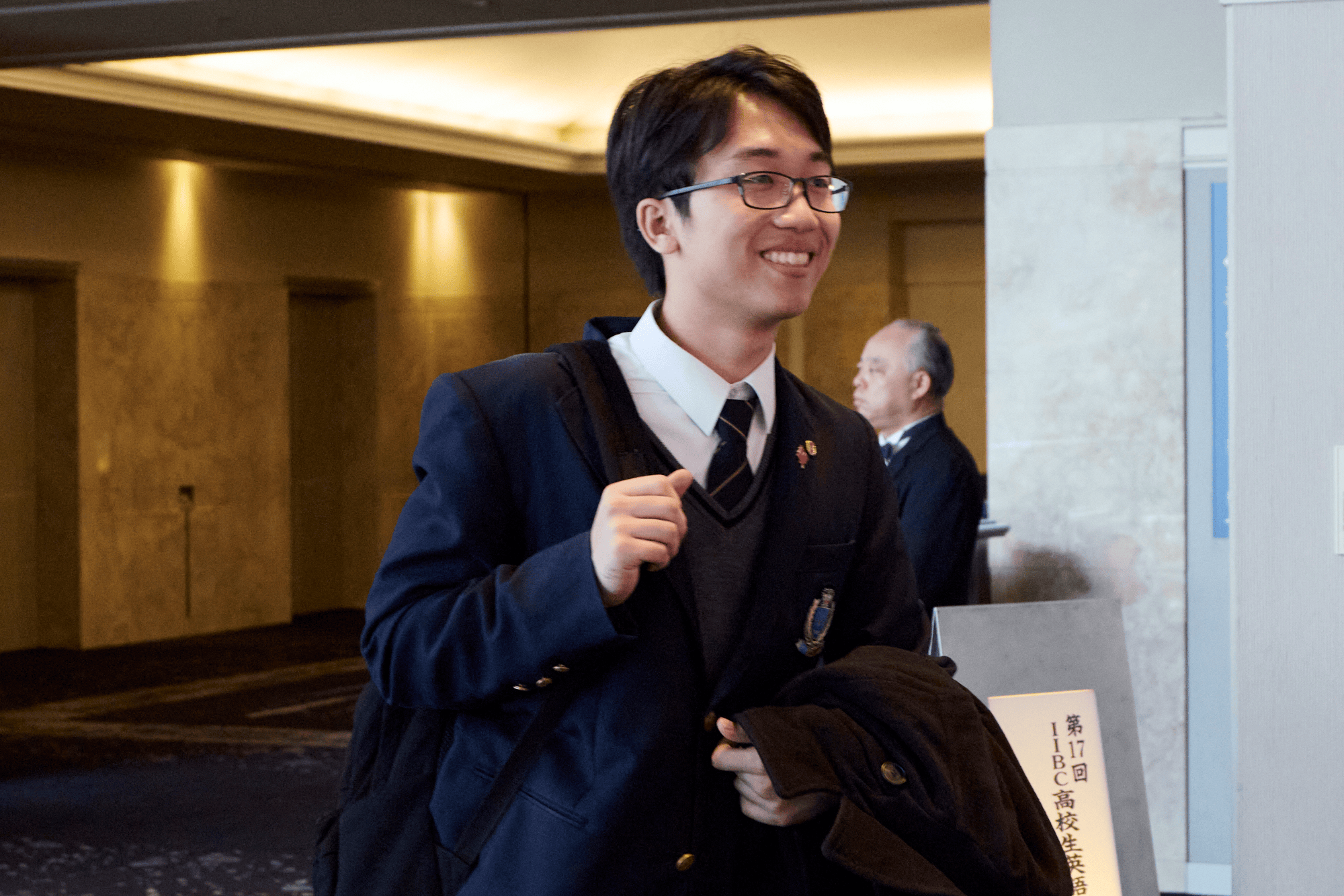

My Passport to the World: How Communication Opened My

Mind

専修学校クラーク高等学院天王寺校 2年

呉 潤希

専修学校クラーク高等学院天王寺校 2年

呉 潤希

今回このコンテストで特別賞をいただき、とても光栄に思います。私は昔から感性が豊かで、小さい頃からよく小説を書いていました。その中でも特に、比喩表現が好きで、今回のエッセイの中でも、グローバルコミュニケーションをパスポートに見立てました。海外に行かずとも、日本の中でたくさんの人々や価値観に出会い、考え方に触れ、学びを重ねることができると気付かされた体験談を綴っています。ぜひ読んでいただけると嬉しいです。

※日米協会会長賞を同時受賞

Cinematic Bridges

高知県立高知丸の内高等学校 3年

岡村 昊虹

高知県立高知丸の内高等学校 3年

岡村 昊虹

この度は素晴らしい賞をいただき、とても光栄に思います。エッセイの作成にあたり、「どのような点に価値観の違いを感じたか」を考えましたが、違いよりも共通点が強く心に残りました。異文化理解とは、違いだけでなく、映画の感動のように世界中の人々と分かち合える共通の繋がりを発見することだと、実体験を通じてお伝えできたことを嬉しく思います。改めて、ご指導くださった先生方、そしてコンテストを開催してくださった皆様に、心より感謝申し上げます。

Finding Harmony Through

Dialogue

近江兄弟社高等学校 3年

小西 琉偉

近江兄弟社高等学校 3年

小西 琉偉

この度は、歴史ある素晴らしい賞を頂き、心から光栄に思います。私は高校二年の夏に訪れたマルタ共和国での留学体験を通して、移民問題が大きな課題となりつつある現代社会において、多文化共生を実現するための「対話の大切さ」についてまとめました。このような私の思いを発表する機会をくださったコンテスト運営者の皆さまに、深く感謝申し上げます。そして、留学を支えてくださった先生方や友人、家族の皆さまにも、改めて心より感謝いたします。

To Quarrel or Debate,

That is the Question

関西創価高等学校 2年

中村 修都

関西創価高等学校 2年

中村 修都

この度は特別賞・アルムナイ特別賞をいただくことができ大変光栄です。

ディベートを高校1年生のときに始めてからというもの、ディベートは、私という人間のかなりの割合を占めてきました。そんなディベートを、一人でも多くの方に深く知ってほしい、との気持ちで書いたエッセイを、こうして評価していただけたことを非常に嬉しく思います。ご指導くださった先生と審査員の皆様に感謝申し上げます。

※アルムナイ特別賞を同時受賞

From Annoyance to

Understanding

報徳学園高等学校 2年

林 悠椰

報徳学園高等学校 2年

林 悠椰

私は小学5年の時に父の仕事の関係でアメリカに渡り、その直後にコロナウィルスによるパンデミックとなりました。そんな生活の中で感じた日米の文化の差、特に表情の捉え方の違い、自身の価値基準だけで人を判断しないことの大切さを文章にしました。私が所属しているラグビー部の活動で時間がない中、コンテストの準備にとても苦労しましたが、このような特別賞をいただき大変光栄に思います。

My Passport to the World: How Communication Opened My

Mind

専修学校クラーク高等学院 天王寺校 2年

呉 潤希

Thank you without saying

仙台育英学園高等学校 1年

圡屋 遼人

HUG - Healing, Understanding, Giving

松山東雲中学・高等学校 3年

西宮 莉杏

松山東雲中学・高等学校 3年

西宮 莉杏

※優良賞と同時受賞のためコメントは省略します。

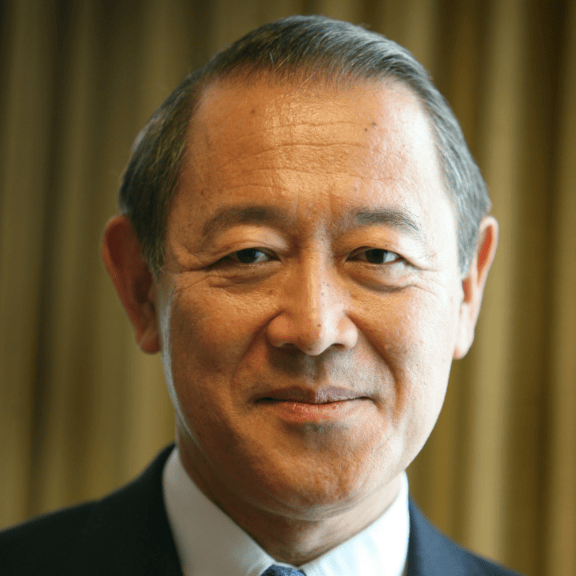

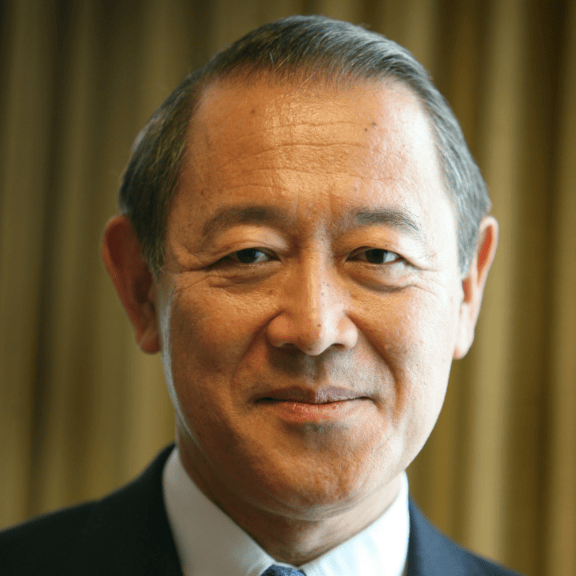

一般社団法人 日米協会 会長

藤崎 一郎氏

本年も応募作品の中から 3 編に「日米協会会長賞」と副賞の記念メダルを差し上げます。

毎年素晴らしい作品が数多く応募されてきましたが、今年は一段とその内容が充実していたようです。このため日米協会での選考審議も大変難しいものになりました。評価にあたっては、印象・インパクト、表現力、テーマとの合一性、そして簡潔性を評点の基軸にし、得られた経験が実践に活かせられるかについても論考しました。受賞した作品はいずれも自らの経験を個性的な表現によって描き出されたとても素晴らしい作品です。

世界の情勢は昨年の今頃に想像していたものとは全く違う様相で急速に変化しています。国際社会の急激な変化が戦争や各国の内政に転換の機会を齎していますが、国際社会という場は間違いなく存続し続けます。皆さんのような若い世代が、国際人として立派に活躍することが、これからの日本にとって大変重要な課題です。皆さんが社会の発展や国際交流に貢献されることを大いに期待しています。

一般社団法人 日米協会 会長

藤崎 一郎氏

本年も応募作品の中から 3 編に「日米協会会長賞」と副賞の記念メダルを差し上げます。

毎年素晴らしい作品が数多く応募されてきましたが、今年は一段とその内容が充実していたようです。このため日米協会での選考審議も大変難しいものになりました。評価にあたっては、印象・インパクト、表現力、テーマとの合一性、そして簡潔性を評点の基軸にし、得られた経験が実践に活かせられるかについても論考しました。受賞した作品はいずれも自らの経験を個性的な表現によって描き出されたとても素晴らしい作品です。

世界の情勢は昨年の今頃に想像していたものとは全く違う様相で急速に変化しています。国際社会の急激な変化が戦争や各国の内政に転換の機会を齎していますが、国際社会という場は間違いなく存続し続けます。皆さんのような若い世代が、国際人として立派に活躍することが、これからの日本にとって大変重要な課題です。皆さんが社会の発展や国際交流に貢献されることを大いに期待しています。

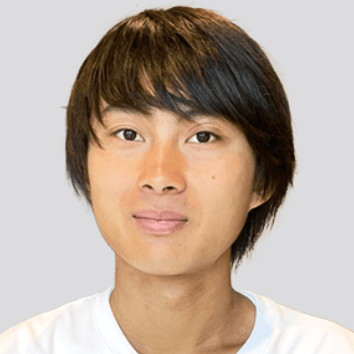

To Quarrel or Debate,

That is the Question

関西創価高等学校 2年

中村 修都

関西創価高等学校 2年

中村 修都

※特別賞と同時受賞のためコメントは省略します。

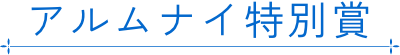

アルムナイ審査員

第15回(2023年)

最優秀賞/日米協会会長賞

第14回(2022年) 特別賞

早稲田大学 国際教養学部 1年

田 哲氏

第16回(2024年)

特別賞・アルムナイ特別賞

・日米協会会長賞

慶應義塾大学 環境情報学部 1年

立石 瑛士氏

第16回(2024年)特別賞

筑波大学 医学群医学類 1年

渡邉 衣氏

審査基準

- 1

独創的な表現

- 2

学びの深さ&発展性

- 3

テーマへの着眼点

選定理由

このエッセイは、ディベートという一つのコミュニケーションの形を通して、筆者自身の鮮烈な体験と内省が丁寧に描かれていました。

特に “Debate is not about fighting—it’s a desperate attempt to understand.” の部分では、ディベートの本質を捉えつつ、逆説的な表現を用いて深い洞察を示しておりました。

また、“Listening as a bridge” という言葉は、筆者が討論を通して得た普遍的な学びを象徴しており、この姿勢は将来、教育・外交・多文化理解といった分野で大いに生かされるであろうと感じさせます。そして、その表現方法は、海外で得られるような特別な経験がなくても勇気さえあれば人は理解し合えることが読み手に伝わりました。

さらに、このエッセイコンテストのテーマとの関係において、「勝敗を超えた理解としてのディベート」という視点は成熟した思考を示しており、読後にも深い余韻と考察を促す優れた作品でした。

以上の点を踏まえて私たち審査員はこの作品がアルムナイ賞に相応しいと思います。

講評

私たちは、このエッセイが持つ表現力と臨場感に圧倒されました。

読み進めるうちに、ディベートというものの本質を改めて考えさせられました。これまで私たちは、ディベートを「相手の論理の弱点を突き、自分の主張を通す」攻撃的なコミュニケーションの一種と認識していました。しかし、それが本来「相手を必死に理解しようとする姿勢」であることに気づかされました。

最後の一文「私はこのディベートに勝ったのだろうか?」は、読者にコミュニケーションの在り方そのものを問いかける印象的な締めくくりで読後にも深い余韻と考察を残す作品でした。

団体部門には、68校より3,936作品ものご応募をいただきました。

次の学校に奨励賞を贈呈します。

鈴木 聡美

吉田 衛

志賀 晴奈

大戸 祥也

井上 陽子

明治大学付属明治高等学校

応募数(学年)

480名 (2,3年生)

指導教諭

横須賀 伴子

静岡県立浜松北高等学校

応募数(学年)

328名 (2年生)

指導教諭

榑松 薫

神奈川県立大和高等学校

応募数(学年)

274名 (1年生)

指導教諭

乾 広樹

岡山県立岡山朝日高等学校

応募数(学年)

214名 (2年生)

指導教諭

村井 容子

本庄東高等学校

応募数(学年)

184名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

ヒューズ・ハナ

女子学院高等学校

応募数(学年)

171名 (2年生)

指導教諭

日比 使門

東京都立三鷹中等教育学校

応募数(学年)

119名 (1年生)

指導教諭

遠藤 遥

鈴木 聡美

吉田 衛

佐賀県立鳥栖高等学校

応募数(学年)

117名 (2年生)

指導教諭

吉田 竜真

香蘭女学校

応募数(学年)

110名 (3年生)

指導教諭

井上 裕子

渋谷教育学園渋谷高等学校

応募数(学年)

96名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

石原 佳枝

エスコラピオス学園海星高等学校

応募数(学年)

82名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

水野 実香

佐賀県立佐賀商業高等学校

応募数(学年)

79名 (2,3年生)

指導教諭

陣内 朋恵

北海道札幌国際情報高等学校

応募数(学年)

72名 (2年生)

指導教諭

阿部 成道

高槻高等学校

応募数(学年)

68名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

横山 貴之

純心女子高等学校

応募数(学年)

68名 (2年生)

指導教諭

大田 晴美

大妻中野中学校高等学校

応募数(学年)

60名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

前川 美樹

富士見丘高等学校

応募数(学年)

56名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

松澤 一徳

立命館高等学校

応募数(学年)

46名 (2年生)

指導教諭

森田 祥子

精道三川台高等学校

応募数(学年)

45名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

村上 和也

岡山高等学校

応募数(学年)

45名 (1年生)

指導教諭

林 秀俊

遺愛女子高等学校

応募数(学年)

43名 (2,3年生)

指導教諭

川嶋 紀子

安城学園高等学校

応募数(学年)

40名 (2年生)

指導教諭

岡村 芳美

東海大学菅生高等学校

応募数(学年)

39名 (1,2,3年生)

指導教諭

菊池 清美

大阪教育大学附属高等学校池田校舎

応募数(学年)

38名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

野村 明日香

神戸大学附属中等教育学校

応募数(学年)

35名 (2年生)

指導教諭

島 安津子

東京都立飛鳥高等学校

応募数(学年)

34名 (2,3年生)

指導教諭

金子 さつき

神奈川県立神奈川工業高等学校

応募数(学年)

34名 (2年生)

指導教諭

村上 雄哉

専修学校クラーク高等学院天王寺校

応募数(学年)

31名 (1,2,3年生)

指導教諭

Scott Gray

愛知県立豊橋東高等学校

応募数(学年)

30名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

岩田 早代

横浜市立横浜商業高等学校国際学科

応募数(学年)

30名 (3年生)

指導教諭

徳永 上総

カリタス女子高等学校

応募数(学年)

30名 (1年生)

指導教諭

島 直子

城南学園高等学校

応募数(学年)

30名 (1,2,3年生)

指導教諭

江村 崇

山梨県立甲府西高等学校

応募数(学年)

29名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

小林 康仁

札幌静修高等学校

応募数(学年)

28名 (3年生)

指導教諭

山口 元貴

三重県立津西高等学校

応募数(学年)

27名 (2年生)

指導教諭

服部 みふみ

八代白百合学園高等学校

応募数(学年)

27名 (2年生)

指導教諭

梅田 貴志

山口県立徳山高等学校

応募数(学年)

27名 (1年生)

指導教諭

秋本 琢也

兵庫県立有馬高等学校

応募数(学年)

25名 (2年生)

指導教諭

井上 柊志

山形県立山形東高等学校

応募数(学年)

25名 (2年生)

指導教諭

折原 寛博

私立幸福の科学学園高等学校

応募数(学年)

25名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

田中 雅徳

愛媛県立松山東高等学校

応募数(学年)

25名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

十亀 麻里

中京高等学校

応募数(学年)

25名 (1,3年生)

指導教諭

麦島 瑛人

岡山学芸館高等学校

応募数(学年)

25名 (2年生)

指導教諭

松本 敦子

鹿児島県立松陽高等学校

応募数(学年)

24名 (3年生)

指導教諭

福留 康代

慶應義塾志木高等学校

応募数(学年)

24名 (2年生)

指導教諭

新保 直毅

広島県立広島国泰寺高等学校

応募数(学年)

24名 (2年生)

指導教諭

鳥生 典江

津田学園中高等学校

応募数(学年)

23名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

堀田涼介

宝仙学園中学校・高等学校

応募数(学年)

23名 (2年生)

指導教諭

對馬 洋介

沖縄県立名護高等学校

応募数(学年)

23名 (2年生)

指導教諭

グリーク 優子

岩手県立南昌みらい高等学校

応募数(学年)

22名 (1年生)

指導教諭

高橋 新哉

法政大学第二高等学校

応募数(学年)

22名 (1,2,3年生)

指導教諭

内田 光治

岡山県立岡山城東高等学校

応募数(学年)

22名 (2年生)

指導教諭

久米 咲絵

志賀 晴奈

大戸 祥也

井上 陽子

北海道札幌東商業高等学校

応募数(学年)

22名 (1,2,3年生)

指導教諭

中川 順一

学校法人呉武田学園武田高等学校

応募数(学年)

22名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

冨山 玲

藤枝明誠高等学校

応募数(学年)

21名 (1,2,3年生)

指導教諭

松永 麻衣子

福岡県立嘉穂東高等学校

応募数(学年)

21名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

三島 典子

京都先端科学大学附属中学高等学校

応募数(学年)

21名 (3年生)

指導教諭

岡野 林太郎

穎明館中学高等学校

応募数(学年)

21名 (2年生)

指導教諭

石川 京子

愛知県立豊田東高等学校

応募数(学年)

20名 (1,3年生)

指導教諭

石塚 さゆり

静岡県立吉原高等学校

応募数(学年)

20名 (1,2,3年生)

指導教諭

コクソン マリオ

白百合学園高等学校

応募数(学年)

20名 (1,2年生)

指導教諭

木幡 秀樹

鹿児島育英館高等学校

応募数(学年)

20名 (2,3年生)

指導教諭

吉田 美和子

頌栄女子学院高等学校

応募数(学年)

20名 (1年生)

指導教諭

橋本 淳

秀明高等学校

応募数(学年)

20名 (2年生)

指導教諭

山本 恭子

日本女子大学附属高等学校

応募数(学年)

20名 (3年生)

指導教諭

行川 満里恵

埼玉県立春日部女子高等学校

応募数(学年)

20名 (1年生)

指導教諭

池上 彩

関西創価高等学校

応募数(学年)

20名 (2年生)

指導教諭

井口 和弘

今回のコンテストに参加いただいた、251校をご紹介します。

北海道・東北

遺愛女子高等学校 / 市立札幌開成中等教育学校 / 北海道札幌厚別高等学校 / 北海道札幌国際情報高等学校 / 北海道寿都高等学校 / 札幌静修高等学校 / 北海道札幌東商業高等学校 / 青森県立三本木高等学校 / 八戸聖ウルスラ学院高等学校 / 岩手県立南昌みらい高等学校 / 仙台育英学園高等学校 / 山形県立山形東高等学校 / 福島県立葵高等学校

関東・甲信越

つくば国際大学東風高等学校 / 茨城県立勝田中等教育学校 / 作新学院高等学校 / 栃木県立佐野高等学校 / 私立幸福の科学学園高等学校 / さいたま市立大宮国際中等教育学校 / 本庄東高等学校 / 開智未来高等学校 / 埼玉県私立東京農業大学第三高等学校 / 埼玉県立戸田翔陽高等学校 / 埼玉県立坂戸高等学校 / 埼玉県立春日部女子高等学校 / 埼玉県立北本高等学校 / 埼玉県立鷲宮高等学校 / 慶應義塾志木高等学校 / 秀明高等学校 / クラーク記念国際高等学校千葉キャンパス / 市川高等学校 / 芝浦工業大学柏中学高等学校 / 渋谷教育学園幕張高等学校 / 成美学園高等學校 / 千葉県立千葉高等学校 / 筑波大学附属聴覚特別支援学校 / 東京学館浦安高等学校 / 東邦大学付属東邦高等学校 / 麗澤高等学校 / NHK学園高等学校 / お茶の水女子大学附属高等学校 / クラーク記念国際高等学校 / 東海大学菅生高等学校 / ドルトン東京学園 / 開成高等学校 / 学習院女子高等科 / 吉祥女子高等学校 / 玉川学園高等部 / 駒込高等学校 / 駒沢学園女子高等学校 / 恵泉女学園高等学校 / 広尾学園高等学校 / 広尾学園小石川中学校・高等学校 / 江戸川女子高等学校 / 香蘭女学校 / 国際基督教大学高等学校 / 三田国際科学学園高等学校 / 私立法政大学高等学校 / 芝国際高等学校 / 淑徳高等学校 / 神田女学園高等学校 / 成蹊高等学校 / 聖学院中学高等学校 / 千代田区立九段中等教育学校 / 早稲田大学高等学院 / 東京学芸大学附属国際中等教育学校 / 東京女学館高等学校 / 東京都立園芸高等学校 / 東京都立国際高等学校 / 東京都立桜修館中等教育学校 / 東京都立拝島高等学校 / 東京都立飛鳥高等学校 / 日本大学豊山女子高等学校 / 八王子学園八王子高等学校 / 普連土学園高等学校 / 宝仙学園中学校・高等学校 / 法政大学高等学校 / 立教池袋高等学校 / 穎明館中学高等学校 / 渋谷教育学園渋谷高等学校 / 女子学院高等学校 / 大妻中野中学校高等学校 / 東京都立三鷹中等教育学校 / 白百合学園高等学校 / 富士見丘高等学校 / 明治大学付属明治高等学校 / 頌栄女子学院高等学校 / クラーク記念国際高等学校SMART横浜キャンパス / クラーク記念国際高等学校横浜キャンパス / フェリス女学院高等学校 / 横浜創学館高等学校 / 横浜中華学院 / 横浜雙葉高等学校 / 鎌倉女学院高等学校 / 慶應湘南藤沢高等部 / 公文国際学園高等部 / 自修館中等教育学校 / 湘南白百合学園高等学校 / 神奈川県立神奈川工業高等学校 / 神奈川県立大和高等学校 / 清泉女学院高等学校 / 聖ヨゼフ学園高等学校 / 聖光学院高等学校 / 洗足学園高等学校 / 日本大学高等学校 / 法政大学第二高等学校 / カリタス女子高等学校 / 横浜市立横浜商業高等学校国際学科 / 日本女子大学附属高等学校 / 新潟県立直江津中等教育学校 / 山梨英和高等学校通信制課程グレイスコース / 山梨県立北杜高等学校 / 日本航空高等学校 / 山梨県立甲府西高等学校 / 長野日本大学高等学校

東海・北陸

富山県立高岡高等学校 / 金沢大学人間社会学域学校教育学類附属高等学校 / 星稜高等学校 / 石川県立七尾高等学校 / 石川工業高等専門学校 / 岐阜県立加茂農林高等学校 / 大垣日本大学高等学校 / 中京高等学校 / 加藤学園高等学校 / 学校法人日本体育大学浜松日体高等学校 / 常葉大学附属橘高等学校 / 静岡県立掛川東高等学校 / 静岡県立吉原高等学校 / 静岡県立沼津東高等学校 / 静岡県立静岡中央高等学校 / 静岡私立静岡英和女学院高等学校 / 静岡雙葉高等学校 / 不二聖心女子学院高等学校 / 静岡県立浜松北高等学校 / 藤枝明誠高等学校 / 名古屋市立名東高等学校 / 愛知県立衣台高等学校 / 愛知県立刈谷高等学校 / 愛知県立御津あおば高等学校 / 愛知県立城北つばさ高等学校 / 愛知県立豊橋東高等学校 / 愛知県立豊田東高等学校 / 愛知真和学園大成中学・高等学校 / 学校法人平山学園清林館高等学校 / 光ヶ丘女子高等学校 / 中京大学附属中京高等学校 / 名城大学附属高等学校 / 安城学園高等学校 / 三重県立四日市高等学校 / 三重県立津高等学校 / 三重県立津西高等学校 / 津田学園中高等学校 / エスコラピオス学園海星高等学校

近畿

近江高等学校 / 近江兄弟社高等学校 / 立命館守山高等学校 / 京都共栄学園高等学校 / 京都市立日吉ケ丘高等学校 / 京都市立堀川高等学校 / 京都聖母学院高等学校 / 京都先端科学大学附属中学高等学校 / 京都文教高等学校 / 東山中学・高等学校 / 同志社国際高等学校 / 平安女学院高等学校 / 立命館宇治高等学校 / 立命館高等学校 / 早稲田大阪高等学校 / 大阪学芸高等学校 / 大阪桐蔭高等学校 / 大阪商業大学堺高等学校 / 大阪朝鮮中高級学校 / 大阪府府立三国丘高等学校 / 大阪府立花園高等学校 / 大阪府立今宮高等学校 / 大阪府立水都国際高等学校 / 大阪府立大阪わかば高等学校 / 大阪府立箕面高等学校 / 東海大学付属大阪仰星高等学校 / 箕面自由学園高等学校 / 関西創価高等学校 / 高槻高等学校 / 城南学園高等学校 / 専修学校クラーク高等学院天王寺校 / 大阪教育大学附属高等学校池田校舎 / 育英高等学校 / 雲雀丘学園中学校・高等学校 / 神戸市立葺合高等学校 / 神戸常盤女子高等学校 / 神戸龍谷高等学校 / 滝川第二高等学校 / 兵庫県立芦屋国際中等教育学校 / 兵庫県立尼崎稲園高等学校 / 兵庫県立有馬高等学校 / 報徳学園高等学校 / 神戸大学附属中等教育学校 / 奈良県立奈良高等学校 / 和歌山県立那賀高等学校

中国・四国

岡山学芸館高等学校 / 岡山県立倉敷鷲羽高等学校 / 岡山県立津山高等学校 / 岡山高等学校 / 岡山理科大学附属高等学校 / 山陽学園高等学校 / 清心女子高等学校 / 明誠学院高等学校 / 岡山県立岡山城東高等学校 / 岡山県立岡山朝日高等学校 / 安田女子中学高等学校 / 学校法人呉武田学園武田高等学校 / 銀河学院高等学校 / 広島女学院高等学校 / 広島大学附属中学高等学校 / 福山暁の星女子高等学校 / 広島県立広島国泰寺高等学校 / 山口県立宇部商業高等学校 / 山口県立徳山高等学校 / 徳島県立徳島北高等学校 / 徳島県立城東高等学校 / 愛媛県立今治西高等学校 / 愛媛県立松山南高等学校 / 愛媛県立西条高等学校 / 愛媛県立西条農業高等学校 / 松山東雲中学・高等学校 / 愛媛県立松山東高等学校 / 高知県立高知丸の内高等学校 / 高知県立高知国際高等学校 / 高知工業高等専門学校 / 明徳義塾中学・高等学校

九州・沖縄

クラーク記念国際高等学校福岡校 / 純真高等学校 / 福岡県立嘉穂東高等学校 / 福岡県立修猷館高等学校 / 福岡県立筑紫丘高等学校 / 福岡県立明善高等学校 / 佐賀県立鳥栖高等学校 / 佐賀県立佐賀商業高等学校 / 純心女子高等学校 / 長崎県立大村高等学校 / 長崎県立長崎東高等学校 / 長崎県立諫早高等学校 / 精道三川台高等学校 / ルーテル学院高等学校 / 八代白百合学園高等学校 / 大分県立別府翔青高等学校 / 日本文理大学附属高等学校 / クラーク記念国際高等学校鹿児島キャンパス / 鹿児島県立松陽高等学校 / 鹿児島育英館高等学校 / 沖縄県立名護高等学校

テーマに沿って皆さんの経験、そこから得た気づきや考えを

「500~700語の英文エッセイ」にして応募してください。

1校あたり3作品まで応募可能です。

賞と審査員

IIBC内の一次審査後、各賞審査員による最終審査で選ばれた作品に以下の賞を贈呈します。

最優秀賞 - 1名

優秀賞 - 1名

優良賞 - 1名

特別賞 - 5名

英語コミュニケーションや異文化理解、グローバルな領域で豊富な経験と知見を有する5名の審査員が、< 構成/分析/例示/創作性/テーマとの整合性/文法・語句 >の観点で選考します。

審査員

東京国際大学 教授

立教大学 名誉教授

松本 茂

桜美林大学 名誉教授

異文化経営学会 会長

馬越 恵美子

ジャパン・インターカルチュラル・コンサルティング

社長

ロッシェル・カップ

公益財団法人

東洋文庫 専務理事

ハーバード大学アジアセンター

国際諮問委員

杉浦 康之

一般財団法人

国際ビジネスコミュニケーション協会

理事長

藤沢 裕厚

日米協会会長賞 - 3名

一般社団法人日米協会が、国際理解や国際交流の観点で優れた作品を選考します。

審査員

一般社団法人 日米協会

会長

藤崎 一郎

一般社団法人 日米協会

専務理事

岡本 和夫

アルムナイ特別賞 - 1名

過去の受賞者(アルムナイ)が審査員となり、独自の観点で優れた作品を選考します。

審査員

第15回(2023年)

最優秀賞・日米協会会長賞

第14回(2022年) 特別賞

早稲田大学 国際教養学部(1年)

田 哲

芦屋学園高等学校1年と2年次に受賞。2回目の応募では、カナダ留学時にホストファザーとの対話から、自分のアイデンティティーに関する悩みが実は強みであったことに気付かされ、その経緯をエッセイにまとめました。人との交流が今の高校生たちにどう影響を与えたのかを見てみたいと思い、審査員に応募しました。

もっと見る

第16回(2024年)

特別賞・アルムナイ特別賞・

日米協会会長賞

慶應義塾大学 環境情報学部(1年)

立石 瑛士

慶應義塾湘南藤沢高等部3年次に受賞。大学では経営学や教育学を学んでいます。

エッセイには、アメリカ在住中の小学生の時に経験した宗教観の違いを認識して得た気づきをまとめました。表彰式にてアルムナイ特別賞審査員の方から伺った選考理由が心に刺さり、私も同じように“書き手の創意工夫が認められる嬉しさ”を還元したいと思い、審査員に応募しました。

もっと見る

第16回(2024年)特別賞

筑波大学 医学群医学類(1年)

渡邉 衣

千葉県立千葉高等学校3年次に受賞。大学では医学を学んでおり、将来は小児科医を志望。

エッセイでは障がいをもつ従姉妹とのやりとりからコミュニケーションのあり方についてまとめました。表彰式では、理系クラスに所属していた私とは異なる価値観、考え方をもつ受賞者と交流でき有意義でした。今年も審査員としてエッセイを読み新たな学びを得たいと考え応募しました。

もっと見る

賞品・特典

最優秀賞

25万円相当のPCまたはタブレット

優秀賞

20万円相当のPCまたはタブレット

優良賞

15万円相当のPCまたはタブレット

受賞者全員

- 表彰状・トロフィー(またはメダル)

- TOEIC® Listening & Reading公開テスト無料受験1回分

- 英語学習プログラム参加

- オープンバッジ(デジタル証明書)

※世界標準規格「オープンバッジ」について

応募者全員

全ての応募作品に英文ライティングのネイティブ講師からのフィードバックを付けて返却します。

テーマに沿って皆さんの経験、そこから得た気づきや考えを

「400~700語の英文エッセイ」にして応募してください。

1校あたり20作品(20名)以上にて応募可能となります(個人部門への応募作品は、この数に含みません)。

賞・参加特典

20作品以上を応募した高校に「奨励賞」を贈呈。

全ての応募作品に英文ライティングのネイティブ講師からのフィードバックを付けて返却します。

APPLICATION DETAILS

応募要項

「個人部門」、「団体部門」のいずれも学校を通じての応募となります。

学校からは両部門に応募可能ですが、生徒個人はいずれかの部門に1作品のみの応募となります。

必ず以下をご確認の上、ご応募ください。

応募受付期間

2025年7月1日(火)~9月16日(火) 15:00

応募資格

以下を満たしていること

英語が母語でない

所在地が日本国内の、「国公私立高等学校・高等専門学校(1~3年)」、または「中等教育学校(4~6年)」に在学している

個人部門

1校あたり3作品まで応募可能。校内選考の実施は各学校のご判断にお任せします。

一次審査、最終審査の結果、 優れた作品に以下の賞を贈呈

- - 最優秀賞(1名)

- - 優秀賞(1名)

- - 優良賞(1名)

- - 特別賞(5名)

- - 日米協会会長賞(3名)

- - アルムナイ特別賞(1名)

審査時には、学校名・生徒氏名は除き、エッセイ本文のみを評価します。

受賞作品については、公式サイト内での発表、当方資料ならびに報道発表資料として利用させていただくため、生徒様の氏名、学年をお伺いいたします。ご応募にあたり予めご了承ください。

団体部門

1校あたり20作品(20名)以上にて応募可能。個人部門への応募作品は、この数に含みません。

団体部門にご応募されたすべての学校に「奨励賞」を贈呈します。

審査結果発表・表彰式

2025年10月下旬以降、公式サイトにて入賞者および入賞作品を発表します。

発表前に、入賞作品の応募校のご担当者様宛に通知します。

表彰式には、受賞者ご本人のほか、指導教員と受賞者のご家族(合計3名まで)を表彰式へご招待します。

2025年度 応募要項【印刷用】PDF

HOW TO APPLY

応募方法

本コンテストへの応募と作品提出はインターネットのみで受け付けます。

両部門とも、窓口となられる先生が応募作品をとりまとめて手続きしてください。

※利用推奨ブラウザ:Google Chrome 最新版 / Firefox最新版

※通信障害等により、個人情報および応募作品を紛失された場合の責任は負いかねますのでご了承ください。

個人部門

エッセイ作品(Wordファイル)のファイル名を、“essay1”、“essay2”、"essay3" とする。

※ファイル名に学校名、氏名は記載しないでください。

本ページ下部に表示される「個人部門に応募する」ボタンより応募フォームにアクセス。

必要事項を入力後、エッセイ作品(Wordファイル)をアップロードして送信。

団体部門

全てのエッセイ作品(Wordファイル)のファイル名に連番をつける。

例)〇〇高校-01.doc、〇〇高校-02.doc

連番をつけた全てのWordファイルを圧縮して1つのファイルを作成する。

ファイルの圧縮形式はZIP形式またはLHA形式としてください。

圧縮したファイルの容量が10MB以上になる場合は、IIBC高校生英語エッセイコンテスト事務局までお問い合わせください。

本ページ下部にある「団体部門に応募する」ボタンより、フォームにアクセス。

必要事項を入力し、2.の圧縮したファイルをアップロードして送信。

※必ず、応募フォームへ入力した「参加人数」と、送付するエッセイの数が同数であることを確認の上、圧縮、送信してください。

FAQ

よくある質問

両方の応募はできません。個人部門もしくは団体部門のどちらか一方をお選びください。

※個人部門は1校あたり3作品まで、団体部門は 1校あたり20作品(20名)以上から応募が可能です。

個人の応募は受付しておりません。

学校単位で応募可能な作品数※を設けておりますので、英語をご指導されている学校の先生に応募のご相談をお願いします。

※個人部門は1校あたり3作品まで、団体部門は1校あたり20作品(20名)以上から応募が可能です。

団体部門は1校あたり20作品(20名)以上から応募が可能です。

19作品(19名)以下での応募は受付しておりません。

※離島や山間部等の学校で、生徒数が上記規定に満たない場合は事務局までご相談ください。

10月下旬を予定しております。

はい。タイトルを除く本文のみの語数をカウントして、エッセイの最後にその語数のご記入をお願いします。

語数と受賞確率は関係ございません。

ご応募される生徒様の母語が英語でなければ、参加可能です。

含まれません。

仙台育英学園高等学校 1年

圡屋 遼人

私が小学校の時、障がいのある同級生が、言葉ではなく静かな行動で感謝を伝えてくれた経験をもとに、「コミュニケーションの本質とは思いであること」、そして「沈黙の大切さ」を書きました。

Thank you without saying

When I was in elementary school, there was a classmate with a disability. He rarely spoke in class and often kept to himself. During lessons, whenever he struggled with something, our teacher would gently ask others to support him. One day, it was my turn.

I remember walking over to his desk, trying to smile and speak kindly. I explained the task slowly and clearly, pointing to things in his notebook and offering help wherever I could. He followed along silently. He didn’t nod, didn’t look me in the eye — just quietly did what I suggested. I tried to tell myself that maybe he was shy, or simply not used to this kind of interaction. But honestly, I was bothered. I had expected something — a small “thank you,” a smile, anything.

After I returned to my seat, I kept looking at him out of the corner of my eye. Nothing changed. He didn’t acknowledge me once. I felt invisible, and maybe a little frustrated. I had done something kind — wasn’t I supposed to feel appreciated? That evening, I kept replaying the moment in my mind. I wasn’t angry at him, but I felt disappointed, and even confused. Maybe I had misunderstood the whole situation.

The next morning, I arrived at school as usual. When I got to my desk, I noticed something new on top of my books: a small card, neatly folded. Inside, written in careful letters, was a simple message: “Thank you.”

There was no name. But somehow, I knew exactly who had left it. His name didn’t need to be there — the message itself carried enough weight. I glanced across the room and saw him quietly preparing for class, just as always. No glance, no wave. Just a quiet presence. But everything felt different now.

That moment changed how I understood communication.

Until then, I had believed that gratitude should follow certain rules — that words or gestures like smiling, nodding, or saying “thank you” were necessary to complete the cycle of kindness. But now, I realized something far more important: gratitude is not about formality — it’s about sincerity. For my classmate, words may not have come easily. But he had taken the time to write a message, fold a card, and secretly leave it on my desk. It was a quiet act, but one filled with thought and care.

This experience made me rethink the very meaning of communication. We often define it in terms of language, tone, and body language. But in truth, communication is simply the effort to connect — to make our thoughts and feelings known, regardless of the method. For some, it’s through speech; for others, through writing, drawing, or action. What matters is not the form, but the heart behind it.

Since then, I’ve become more attentive to the silent ways people express themselves — the friend who sits beside you without saying a word when you’re feeling down, the stranger who holds the door a little longer than usual, the sibling who leaves your favorite snack on the table without a note. None of these things is spoken, but they are all forms of communication — and in many ways, they speak louder than words.

Looking back, I’m grateful that I was “bothered” by the silence. If I hadn’t felt that discomfort, I might never have noticed the beauty in that quiet gesture the next day. Sometimes, a gap or a silence is not a lack of connection — it is an invitation to listen more carefully.

The world is full of unspoken messages. We just have to be open enough — and quiet enough — to hear them.

Today, I believe that the most powerful connections are built not only through eloquent words or grand gestures, but through small, heartfelt acts that often go unnoticed. A folded piece of paper. A handwritten note. A silent “thank you.” These are the things that truly connect us.

洗足学園高等学校 5年

菅原 俐亜

聴覚に障がいのあるダンサーとの出会いを契機に、言葉を超えた心のつながりを学んだ経験を綴りました。違いを受け入れ、互いを理解し合うことで得られる新たな気づきを、読者の皆さまにも共に感じ取っていただければ幸いです。

Flight

If I could choose any superpower, I would choose to fly. The idea of weightlessness, of defying gravity and moving untethered through the air, had followed me since childhood. That’s how I found my wings not in the sky, but in the dance studio. There, surrendering to the onset of music, I discovered how to dissolve weight and time. With adrenaline coursing through me, each movement felt like an ascent, each beat like a gust of wind carrying me higher.

It was during one of our breakdance ciphers, those spontaneous circles where we each displayed our creativity to whatever song the speakers demanded, that I first noticed him. The smallest in the room, barely eight years old, and the only one dancing just slightly off-beat. At first, it barely registered. Every beginner stumbles. But over time, I noticed a few things. There was his silence, the way he never responded when the instructor called across the room. There were the hushed, frequent meetings between his mother and the teacher. And then there was the hand signal.

It happened during a water break, when I offered him a snack. He lifted one hand to his chest and moved the other in a sharp line from his forehead to his arm. The motion was deliberate, practiced, too precise to be meaningless. I returned his gesture with a smile, though inside questions began to gnaw at me.

What was that? Why had he done that? What did it mean?

By the time class ended, my mind buzzed with restless curiosity. On the train ride home, a flood of questions began to overtake my search bar until, at last, the screen revealed the answer. It was JSL, Japanese Sign Language, for “thank you.”

The revelation unraveled the puzzle. The teacher’s careful enunciation. The boy’s delayed responses unless tapped on the shoulder. His uncanny habit of moving with the bass instead of the lyrics. He was deaf. What I had mistaken for “off beat” was simply a different rhythm altogether. Yet this clarity left me unsettled. One question remained, lodged stubbornly in my mind.

What was he doing in breakdance?

The thought embarrassed me even as it formed, but it was genuine. Breakdance is a style defined by headspins, freezes, and footwork intertwined with musical nuance. Even with my hearing intact, keeping time was a challenge. How could someone who could not hear the music possibly hope to master it?

Hoping for an answer, I resolved to watch him, to look closer. As the music thundered from the speakers, I noticed his ritual. Before stepping into the cipher, he crouched low, palms pressed flat against the wooden floor. The bass reverberated through the studio, vibrating the ground, and he seemed to absorb it through his hands, letting the vibrations overtake his body. He wasn’t following the same beat I heard; he was translating vibration into rhythm, silence into motion. He wasn’t off beat, he was attuned to something deeper. Then, he stretched his wings and took flight.

For the first time, I saw him not as the youngest student in the class, or as a mystery to decode, but as a dancer. Watching him ride the invisible currents of music that only he could feel, I understood him. In his dance, I recognized my own longing. This boy who, like me, had come here to fly.

I never knew his name, but he showed me that communication can transcend language, culture, and even silence. In a world where differences are shunned and discriminated upon, he taught me that our differences are not obstacles, they are wings, carrying us toward new ways of expression, new ways of connection.

To the boy who gave me this lesson, and reminded me of the power our wings hold: thank you.

松山東雲中学・高等学校 3年

西宮 莉杏

1カ月間のアメリカ留学。私の心を強く捉えたのがハグでした。はじめて交わしたハグ。心をつなぐものでした。オバマ元大統領が広島訪問で見せたハグ。HUGの持つ力 (Healing, Understanding, Giving) と平和の願いを伝えたくてエッセイにしました。

HUG - Healing, Understanding, Giving

While studying in the United States, I exchanged hugs with many Americans. It wasn’t just during special occasions—hugs happened when we first met, when saying goodbye, and in many everyday moments. Hugging is a natural part of American culture. At first, I couldn’t hide my confusion. I had never experienced such casual physical closeness. But over time, I got used to it and began to understand the quiet power of a hug.

Before I embraced this custom, I felt distant from others. I couldn’t speak English well, and I doubted whether I could truly connect with people. But as I grew more comfortable with hugging, I felt a sense of security begin to form between me and the Americans around me. It was as if the simple act of a hug allowed me to be seen and accepted, even without words.

As I became more familiar with hugs, I began to recall a powerful image from my childhood: the hug between former President Barack Obama and a Japanese man in Hiroshima. In May 2016, President Obama visited Hiroshima—the first sitting U.S. president to do so—and delivered a speech calling for a world without nuclear weapons.

During the event, a Japanese man invited by the American side approached Obama. He wanted to thank the president in his own words, without an interpreter. But overwhelmed by emotion, he became speechless. His body trembled, and tears ran down his cheeks. In that moment, President Obama embraced him.

Later, the man said, “I think the purpose was to calm me down. Since we couldn’t exchange words, the hug became our way of communicating. It gave me a sense of security.” That moment, brief but full of meaning, was reported widely in both Japan and the United States. It became a symbol of peace—a hug between two people from nations once divided by war.

A hug is the most peaceful weapon we can offer each other. Unlike conventional weapons that cause pain and division, a hug brings comfort, healing, and connection. Its silent touch speaks louder than words, melting anger and fear without a single blow. Whether between friends, strangers, or even former enemies, a hug has the power to restore trust and humanity. In a world often torn by conflict, this gentle gesture reminds us that peace begins with empathy.

Psychologists say hugs trigger oxytocin, the “love hormone.” It calms the body, lowers stress, and strengthens emotional bonds. But beyond science, hugs speak to the human heart. A friend I met in America once told me, “A hug shows love and gives comfort—not just to the person receiving it, but also to the one giving it.” I believe that hugs offer something even greater: a quiet kind of peace.

Nelson Mandela once said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” I believe hugs are powerful too—not in force, but in peace. A hug doesn’t destroy—it heals. It doesn’t divide—it connects. Just like education opens minds, hugs open hearts. And when minds and hearts are open, the world can truly change.

Through my experiences in America and the memory of Hiroshima, I’ve come to believe that hugs are more than gestures. They are symbols of hope, understanding, and grace. In Japan, where hugging isn’t part of our culture, I don’t wish to erase tradition—but I do hope people become curious. Even a small interest in the culture of hugging could lead to deeper connections across borders.

I dream of a society where people can meet across borders without fear—where cultural differences open doors, not close them. In such a world, even a simple hug can become the first step toward peace. Quietly and gently, a hug allows us to communicate compassion with each other, reminding us that true connection often begins without words.

I believe HUG stands for Healing Heart, Understanding Uniqueness, and Giving Goodwill. Let’s walk the path of healing and cross the bridge of understanding together. And let your “light of giving” shine. The world is waiting for us where our hearts unite.

専修学校クラーク高等学院天王寺校 2年

呉 潤希

このエッセイは、コミュニケーションを世界へのパスポートとして描いています。交流や異文化体験、友人を守る行動を通して、共感や勇気、視野の広がりを学び、成長や人との関わりの大切さを示した作品です。

My Passport to the World: How Communication Opened My Mind

When I think of the word communication, I imagine a passport. Without it, I would be stuck in a small nation called “my own thoughts.” By picking up a passport called communication, I’ve traveled the world, without ever leaving my room.

In the beginning, my mind was like a blank passport: full of potential, but without a single stamp. I spoke only my native language, interacted with people just like me, and saw the world through a narrow lens. But everything changed when I moved to an international school in fourth grade. Suddenly, I found myself surrounded by classmates from different countries, cultures, and belief systems. This shift introduced me not only to new languages, but to new ways of thinking. That’s where my journey toward global awareness truly began.

I began speaking not only with my close friends, but also with students from other grades, different backgrounds, and even teachers I once found intimidating. At first, it felt awkward to approach unfamiliar people, especially in a second language. I used to hold a strong prejudice against foreign people when they try to get into someone’s hearts very forcibly. However, those moments of discomfort led to the deepest lessons about people. Some teachers, despite seeming strict, turned out to be incredibly supportive. Their kindness taught me that preconceptions often dissolve through open dialogue, even a word or phrase, like “excuse me” and that communication has the power to reshape the way we see others.

The most memorable day at my school was when I stood up for a girl in my class who was being teased because of her accent in speaking, shaped by her Indian background. At first, I hesitated, because I had always kept myself comfortable and did my best to not be involved in problems. Then I remembered how significant it is to use our voices when it is needed by someone. That small act felt like a moment of bravery, not only for her, but for myself. A few weeks later, she invited me to her house for her birthday. Her family welcomed me with warmth, and she served me traditional Indian food I had never tasted before. The food was delicious, but even more than that, the experience left a lasting emotional impression. Her quiet kindness and gratitude taught me that cross-cultural exchanges don’t always happen in classrooms; sometimes, they happen around the dinner table. I would never forget the day I spoke up, because we ended up being good friends until graduation.

Through these experiences, I gained something far greater than just language skills: I experienced perspective shifts that shaped my values. Through these shifts in perspectives, I learned the importance of empathy, the courage to speak up, and the strength found in communities that support one another. Communication became more than just a tool for conversation, it became a mirror that reflected who I was, and a window into how much more there was to understand, giving me much more chances to rethink about my all-day activities. For me, communication now holds more power than any subject, sport, or school event I’ve ever participated in.

Looking back, I now realize how communication has transformed my worldview and my identity. What started as an empty passport has slowly filled with invisible stamps: acts of kindness, shared stories, and emotional growth built through authentic connection. Communication has not just broadened my horizon. It has deepened it by layers, through every conversation, every challenge, and every new voice I’ve heard. Although I used to be timid and afraid to speak up, I had made a significant step forward to get excited about being aware of different perspectives and feelings. I still have many blank pages in my passport, but now, I’m excited to fill them: one conversation at a time.

高知県立高知丸の内高等学校 3年

岡村 昊虹

オンラインで出会ったイギリスの友人と語り合う中で、国が違っても同じ映画に心を動かされる瞬間があると知りました。そんな共通の気持ちが、異文化の壁を越える力になることを伝えるエッセイです。

Cinematic Bridges

Is cross-cultural understanding really just about understanding differences? People often think that cross-cultural communication is to find big differences in values, customs, and ways of thinking, and that learning about these differences is the most important thing. It is true that we can learn a lot from differences. However, my experience has been just as valuable—and even more surprising. It has told me that even people from completely different countries and backgrounds can discover unexpected commonalities that bring them closer together. I’ll talk about common ground with one foreigner, and common ground with people around the world.

First, I realized that sharing the same interests can connect hearts across cultural differences while discussing movies with my British friend. I met him through a language exchange app Hello Talk which allows people around the world to practice languages, make friends, and learn about other cultures. One day, while having a casual chat on HelloTalk, I asked my friend, “Do you have any movie recommendations?” Without hesitation, he recommended two movies to me: “Shutter Island” and “Fight Club”. I had never seen either of them before, but just listening to his description made me excited to watch them. Feeling curious, excited, and a little nervous, I decided to watch both movies on my day off, hoping they would be as good as he said. Both movies had surprising twists at the end. I was completely absorbed, and even after watching them, I felt joy knowing I shared the same sensibilities with people from different cultures. From my friend’s perspective, he was simply sharing a movie he liked and wanted me to enjoy it too, without being conscious of cultural differences. However, this simple act led to the discovery of commonalities across national borders.

Secondly, I realized that I share the same feelings not only with one foreigner but with people all over the world. I kept thinking about “Shutter Island” and “Fight Club” for a long time and looked at various people’s interpretations of the stories. I thought these movies might only be popular overseas, and that my friend’s taste in movies would be very different from Japanese taste in movies. However, after doing some research, I realized that I wasn’t the only one shocked by the twists in both movies. People around the world wrote about watching the entire movie again to catch every detail they had missed the first time. Just like me, they were stunned by how everything they thought they knew flipped in an instant. This shared astonishment made me realize that despite different cultures and languages, we all responded to those shocking scenes in the same visceral way. I thought I would find completely different opinions and values, but in fact, we discovered that we already shared meaningful and enjoyable things, and this gave us an unexpected sense of excitement and closeness.

My experience made me realize that sometimes we focus too much on differences. What truly connects people may be simple things, such as enjoying the same stories, feeling the same excitement, and sharing the same joys. Through this experience, I realized that cross-cultural communication is not just about discovering differences. True communication is discovering that sharing joy and interest, and the simple connections that come from them, can bring people closer together than learning about cultural differences. This experience taught me that cross-cultural communication is not about creating barriers between differences, but rather about building bridges of understanding, connection, and shared enjoyment around the world.

In conclusion, intercultural communication is not about finding differences or pointing out what divides us. It is more important to share moments, discover commonalities, and realize that we can connect with each other through the things we love, no matter where we are in the world. Cross-cultural communication is not a barrier but a bridge that connects hearts and minds across distances, cultures, and even language differences.

近江兄弟社高等学校 3年

小西 琉偉

マルタ留学での異文化交流を通して、異文化理解や対話の大切さを学んだ経験を綴ったものです。京都のオーバーツーリズム問題や埼玉県川口市の移民問題など、日本社会が抱える多文化共生の課題を踏まえたうえで、日本で真の多文化共生社会を実現するために何が必要かを見つめ直しました。

Finding Harmony Through Dialogue

At first, the phrase “Let’s build a multicultural society” sounds simple, even obvious. However, behind it lie many challenges. In Kyoto, an overflow of tourists has caused serious problems for local communities. In Kawaguchi, Saitama, tensions toward the Kurdish community escalated into large-scale protests. As globalization advances in Japan, we face a profound question—should we welcome immigrants or turn them away? Simultaneously, we must consider how to truly understand and connect with different cultures and live together in harmony.

Seeking a way to protect Japan’s traditions and values while opening our hearts to the world, I applied for the Tobitate! Study Abroad Initiative and traveled to Malta, a small island in the Mediterranean Sea. Throughout its long history, Malta has been ruled by many nations, but it has consistently embraced new cultures while carefully preserving its own. It was the perfect place to learn the delicate balance between coexistence and tradition.

At language school, I studied alongside classmates from Europe, Africa, and South America. Initially, I felt isolated and struggled with English, yet over time my confidence grew. After class, we would sit by the sea at sunset, sharing stories about our homes. I spoke about Japan’s samurai spirit, Hafed from Libya described the beauty of his desert, and Zoé from Belgium shared photos of traditional sweets. We laughed, sometimes grew serious, and discussed the challenges facing our countries. In those conversations, I felt the quiet still profound power of dialogue.

One moment that stands out in my memory is during a “cultural presentation” class, where I introduced Japanese calligraphy, explaining that it embodies a calm heart and focused mind—the very spirit of wa, or harmony. Hafed confidently brushed the word Peace and said, “This is what my country needs.” In that instant, I felt a spark of hope. I realized that cultural exchange does not diminish tradition but deepens understanding and strengthens our desire to protect it.

As part of my research, I interviewed my host mother, Grace. When I asked how she felt about the growing number of immigrants and students in Malta, she paused thoughtfully and said, “Of course, differences can make us uneasy, but Malta has always grown together with many cultures. We don’t push people away; we welcome them while preserving our own heritage. The important thing is not to fear differences, but to talk and discover how to live together.” Her words moved me deeply. Malta’s coexistence is not just a slogan—it is wisdom shaped by history. Japan may need time, yet we have much to learn from this approach.

After returning home, Hafed and I organized an online meeting connecting Libyan youth with Japanese high school students on the theme “Our Peace.” At first, everyone was shy, but gradually the conversation grew warm as we listened, empathized, and tried to understand each other. Through this cross-border exchange, I once again felt the powerful force of dialogue. One scene remains particularly poignant: a Japanese student spoke to a Libyan friend who had lost his parents in war, saying, “This exchange reminded me how precious peace is; Japan needs more talks like this if we want to walk with the world.” Hafed nodded softly, his eyes full of quiet understanding.

In the years ahead, tourism and immigration will surely increase, and a multicultural society will inevitably arrive in Japan. To protect our traditions and people’s hopes, we need the courage to connect hearts and the strength of dialogue: to confront misunderstandings, learn about differences, and build a future grounded in respect. Japanese people are often described as reserved, and silence can sometimes allow misunderstandings to grow—yet if we dare to speak and explore our differences together, we may find a way to live as true neighbors.

My journey has only just begun. I want to continue creating spaces in Japan where diverse cultures and values can meet and resonate, as my friends in Malta taught me this truth: the answer to Japan’s future lies within those conversations. It is through these conversations where hearts truly meet across cultures that we can shape a Japan that honors both its traditions and its openness to the world.

関西創価高等学校 2年

中村 修都

本作品では、ディベートというコミュニケーションの力が、私をどう変えたのか、ということを書きました。ディベートの秘めるコミュニケーションの力について少しでも知って頂く、もしくはディベートを始めるきっかけになれば幸いです。

To Quarrel or Debate, That is the Question

The judge’s final word echoed in the silent room: “The winner is… the affirmative side.” We lost. The match that would have sent us to the tournament was over. Yet, in that moment of defeat, I felt not the sting of disappointment, but an electrifying connection to the very rivals who had just bested us. We had thrown every ounce of our logic and passion at each other, and in the aftermath, what remained was not bitterness, but a profound, shared respect. This was not a quarrel. This was debate.

Many people imagine debate as a civilized form of fighting, but they often aren’t right. It is not about fighting at all; it is about a desperate attempt to understand. To debate a topic like ‘green energy’ for instance, is not merely to list facts and figures. It is to force yourself into the shoes of an environmental activist watching glaciers melt, and simultaneously into the worn-out boots of a coal miner whose job is the only thing feeding his family. I remember arguing fiercely for carbon taxes, and as my logic cornered my opponent, I felt a surge of victory. But that night, I thought of the imaginary miner I had rendered jobless.

My argument was sound, my logic impeccable, but my heart ached with a strange sense of guilt. The world, I realized, was not a clean syllogism of right and wrong. It was a messy, complex, and also beautiful tapestry of conflicting truths. Truth is not only one. My world didn’t just expand with new knowledge; it deepened with the weight of human complexity.

This lesson was hard-won. When I first started debate, I was a child wielding words and evidence like knives. I saw opponents not as people, but as arguments to be dismantled. My goal was just to listen only for their weaknesses, to find the cracks in their logic and devastate them. I was often successful, but I was never connecting. When I lost a match, I often blamed opponents or even judges.

The turning point came in a devastating loss against a team from another high school. I was selfish and naive. They didn’t just refute my points; they respectfully took them and gently showed me a much larger picture I hadn’t seen. I was silenced not by aggression, but by their profound understanding. In that humbling defeat, I learned the true art of listening: not as a tool for rebuttal, but as a bridge to another’s reality. Connecting our hearts doesn’t begin with speaking; it begins with the courageous act of truly wanting to understand.

In the end, I believe the most meaningful journeys are not measured in kilometers. While a plane ticket can show you a different part of the world, a willingness to engage in structured, respectful dialogue can show you a different world within another person. Emotional arguments build walls that imprison us in our own perspectives. But debate, in its ideal form, provides the tools to build a bridge—a bridge built of logic, empathy, and a shared set of rules.

To truly connect our hearts and expand our world, we don’t need to cross oceans. We just need the courage to cross the space between ourselves and another, to listen, and to see the world, for a moment, through someone else’s eyes. This journey of understanding has no final destination; it is a path I have only just begun to walk. If you’re looking to take a similar first step—to build your own bridges—I can definitely recommend a place to start.

Now, did I win this debate?

報徳学園高等学校 2年

林 悠椰

私は、米国でのコロナ禍に感じた日米の文化差、特に表情の捉え方の違いを文章にしました。これからも、自身の価値基準だけで人やその行動を判断しないオープンマインドネスを大切にしていきます。

From Annoyance to Understanding

“I HATE MASKS!!!” Oh no, not again. That was the thought I had every time I heard someone shouting those words. When the COVID-19 pandemic occurred, I was living in America for my father’s job. During that period, many countries mandated people to wear masks to prevent the virus from spreading. However, many people in America did not like wearing them.

Growing up in Japan, wearing masks was nothing special. I had often worn them when I got sick or just to prevent myself from getting sick. Because of this, I did not understand why Americans hated masks so much. To be honest, I grew so tired of and annoyed by hearing those three words— “I hate masks.” I kept wondering, “Why can’t they just get used to wearing them?”

One time, I asked my friend why he hated wearing masks. He told me, “First of all, masks are just uncomfortable. Plus, they make it hard to communicate with each other. You can’t read people’s facial expressions when they’re wearing one.” His first reason was quite understandable, but his second reason puzzled me. I had never felt that way before. His point intrigued me, so I decided to think about it more deeply on my own. It was then that I realized that Japanese and Americans value different things in communication.

Japanese are known to express their thoughts and ideas indirectly. We often imply our honest thoughts in conversation, so we tend to try to understand people’s true feelings from small details like eye movements. Americans, on the other hand, value conveying their opinions clearly in words. This difference led me to the idea that during a conversation, Japanese tend to focus on a person’s eyes, while Americans focus on their mouth. Americans feel they cannot read other people’s facial expressions when their mouths are covered by things like masks. In contrast, Japanese often feel a sense of unease when a person’s eyes are covered by sunglasses, as it becomes difficult to read their expressions. In fact, I have often heard Japanese people say that wearing sunglasses makes people look “scary” for that exact reason. I also found another fascinating difference when I compared Japanese and American emojis. For example, the Japanese emoji (Kaomoji) (^_^) indicates happiness, while (>_<) indicates struggle. These two emojis convey completely different emotions, yet the shape of the mouth remains the same—just a line. In contrast, American emojis such as :) and :( express smile and sadness, respectively. They convey two different emotions, but the shape of its eye stays the same—just two dots. Taken together, these examples clearly show our contrasting communication style. While Japanese rely on the eyes to convey emotions, Americans use the mouth as the primary indicator of feeling. It shows how deeply rooted these different ways of communicating are in our respective cultures, even in something as modern and casual as digital communication.

Through these discoveries, I realized that Japanese and Americans value different aspects of communication. At the same time, I was struck by the danger of judging people based solely on their behavior. I used to be annoyed by people shouting, “I hate masks!” I viewed them as people who simply complained without putting in much effort. Now, however, I understand that there was a reason behind their view: a reason rooted in their cultural background. This experience taught me a profound lesson that when we encounter behavior or ideas that are unfamiliar or difficult to understand, we should choose to accept them with an open mind. We must look beyond the surface and seek to understand the reason behind someone’s actions. I believe that this willingness to understand is the essence of true communication. By learning to see beyond our own cultural lens, we take our first step toward building bridges instead of walls. These bridges allow us not only to connect with people from different backgrounds, but also to discover new perspectives, ideas, and values, turning differences into opportunities for deeper understanding and mutual respect.

東京国際大学 教授

立教大学名誉 教授

松本 茂氏

今年の応募作品は、昨年よりもさらにレベルが一段と上がり、読み応えのあるものばかりで、順位をつけるのに大変苦労しました。冒頭でテーマを提示しつつ読み手の心をつかむことに成功しているエッセイばかりでした。また、個人的な体験から学んだことを説明して終わりといった単純な構成ではなく、具体的な体験に抽象的な概念をリンクさせているエッセイが多かったのも驚きでした。さらに、比喩を上手に使ったり、ほぼ同じことを類義語で説明したりするなど、巧みな表現力は高校生のレベルをはるかに超えているエッセイが多かったです。コンテストのテーマであるコミュニケーションとは「人とのつながりにおいて、意味を構築するプロセス」です。つまり、同じ事象から何を学びとるかどうかは、人それぞれです。今回エッセイを書くことでこれまでの体験の意味を振り返ったように、日々「振り返り」を忘れないようにするとよいでしょう。

桜美林大学 名誉教授

異文化経営学会 会長

馬越 恵美子氏

「コミュニケーションを通じた響きあい」。どのエッセイにもこのテーマが深く感じられました。ひとつひとつのエッセイに、それを書いた方の体験と感動がちりばめられています。異なる内容でも、そこに共通して流れているものは、違いを乗り越えて、分かり合うことの大切さ、ではないでしょうか。若いときに、多様な価値観に触れているからこそ、つながることの大切さ、そしてそこから広がる世界が、自分事としてわかるのですね。エッセイコンテストに参加したすべての若人たちに、エールを送ります。そして、必ずや、今回の経験が大きな宝となって、将来に渡って、いろいろな場面で励みになると確信します。混沌とした世界にあっても、自分の信じるところを貫いて、道を切り開いていってください。期待しています。

ジャパン・インターカルチュラル・コンサルティング

社長

ロッシェル・カップ氏

With so much of the rhetoric in the public sphere focused on dividing people and encouraging suspicion of people who are different, reading these essays feels like a breath of fresh air. Whether traveling to a faraway land or simply paying closer attention to the people around them, these students are opening themselves to understanding and empathizing with those who are different from themselves.

公益財団法人 東洋文庫 専務理事

ハーバード大学アジアセンター国際諮問委員

杉浦 康之氏

本年も多くの素晴らしい作品に出会うことができた。新たな発見に繋がる観察力や、研ぎ澄まされた感性には心を動かされたし、日本の将来を託することができる人材に巡り合えたような気持ちになった。異文化を論じる際は相違点よりも共通点を見出すことが重要だとの指摘や、課題に対する答えは必ずしも一つではないとの指摘は、自らの体験から導かれているからこそ価値がある。作品の中には、ロシア・ウクライナ紛争やパレスチナ和平について論じたものがあったが、難しい時事問題から逃げず、当事者の立場になって真剣に考えたことは貴重な経験と言えよう。読み応えのあるエッセイが多かったものの、決めてとなったのは、発想が斬新か、分析が表面的でないか、社会にインパクトを与え得る主張かと言った点であったと思う。これからも是非君たちの叡智で、社会を変革していって欲しい。

一般財団法人 国際ビジネスコミュニケーション協会(IIBC) 理事長

藤沢 裕厚氏

今年も多くの応募の中から優秀作を選ぶことは非常に難しい仕事でした。

エッセイのテーマは「つながる心、広がる世界 コミュニケーションを通じた響きあい」ですので作品を評価するうえで重点を置いたのは ①どのような場面で心がつながったと感じたのか ②コミュニケーションがとれたことにより今までの考え方や社会を見る目がいかに広がったのか の2点を分かり易く表現出来ているかどうかということでした。多くの作品が海外での生活や留学体験に基づくものでしたが、一方で日本における日常生活の中でのこころの通じ合いを取り上げた作品も今年は多く寄せられていて、その中にはその結果いかに世界が広がったかを巧みに表現できている作品も見受けられ、このような作品が今後も増えていってほしいと感じました。

東京国際大学 教授

立教大学 名誉教授

松本 茂氏

今年の応募作品は、昨年よりもさらにレベルが一段と上がり、読み応えのあるものばかりで、順位をつけるのに大変苦労しました。冒頭でテーマを提示しつつ読み手の心をつかむことに成功しているエッセイばかりでした。また、個人的な体験から学んだことを説明して終わりといった単純な構成ではなく、具体的な体験に抽象的な概念をリンクさせているエッセイが多かったのも驚きでした。さらに、比喩を上手に使ったり、ほぼ同じことを類義語で説明したりするなど、巧みな表現力は高校生のレベルをはるかに超えているエッセイが多かったです。コンテストのテーマであるコミュニケーションとは「人とのつながりにおいて、意味を構築するプロセス」です。つまり、同じ事象から何を学びとるかどうかは、人それぞれです。今回エッセイを書くことでこれまでの体験の意味を振り返ったように、日々「振り返り」を忘れないようにするとよいでしょう。

桜美林大学 名誉教授

異文化経営学会 会長

馬越 恵美子氏

「コミュニケーションを通じた響きあい」。どのエッセイにもこのテーマが深く感じられました。ひとつひとつのエッセイに、それを書いた方の体験と感動がちりばめられています。異なる内容でも、そこに共通して流れているものは、違いを乗り越えて、分かり合うことの大切さ、ではないでしょうか。若いときに、多様な価値観に触れているからこそ、つながることの大切さ、そしてそこから広がる世界が、自分事としてわかるのですね。エッセイコンテストに参加したすべての若人たちに、エールを送ります。そして、必ずや、今回の経験が大きな宝となって、将来に渡って、いろいろな場面で励みになると確信します。混沌とした世界にあっても、自分の信じるところを貫いて、道を切り開いていってください。期待しています。

ジャパン・インターカルチュラル・コンサルティング

社長

ロッシェル・カップ氏

With so much of the rhetoric in the public sphere focused on dividing people and encouraging suspicion of people who are different, reading these essays feels like a breath of fresh air. Whether traveling to a faraway land or simply paying closer attention to the people around them, these students are opening themselves to understanding and empathizing with those who are different from themselves.

公益財団法人 東洋文庫 専務理事

ハーバード大学アジアセンター

国際諮問委員

杉浦 康之氏

本年も多くの素晴らしい作品に出会うことができた。新たな発見に繋がる観察力や、研ぎ澄まされた感性には心を動かされたし、日本の将来を託することができる人材に巡り合えたような気持ちになった。異文化を論じる際は相違点よりも共通点を見出すことが重要だとの指摘や、課題に対する答えは必ずしも一つではないとの指摘は、自らの体験から導かれているからこそ価値がある。作品の中には、ロシア・ウクライナ紛争やパレスチナ和平について論じたものがあったが、難しい時事問題から逃げず、当事者の立場になって真剣に考えたことは貴重な経験と言えよう。読み応えのあるエッセイが多かったものの、決めてとなったのは、発想が斬新か、分析が表面的でないか、社会にインパクトを与え得る主張かと言った点であったと思う。これからも是非君たちの叡智で、社会を変革していって欲しい。

一般財団法人 国際ビジネスコミュニケーション協会(IIBC)

理事長

藤沢 裕厚氏

今年も多くの応募の中から優秀作を選ぶことは非常に難しい仕事でした。

エッセイのテーマは「つながる心、広がる世界 コミュニケーションを通じた響きあい」ですので作品を評価するうえで重点を置いたのは ①どのような場面で心がつながったと感じたのか ②コミュニケーションがとれたことにより今までの考え方や社会を見る目がいかに広がったのか の2点を分かり易く表現出来ているかどうかということでした。多くの作品が海外での生活や留学体験に基づくものでしたが、一方で日本における日常生活の中でのこころの通じ合いを取り上げた作品も今年は多く寄せられていて、その中にはその結果いかに世界が広がったかを巧みに表現できている作品も見受けられ、このような作品が今後も増えていってほしいと感じました。